Did the 80's Have the Most One-hit Wonders?

So this was a question that my family and I were asking ourselves as we listened to T’Pau’s “Heart and Soul” on a recent road trip.

And it got me to thinking — when I asked my friends, co-workers, or random strangers on the street, everybody seemed to agree that 80s were the golden era of one-hit wonders. But was this actually the case? Did the 80s really have the most one-hit wonders? Or is this just one of those facts that we all assume is true, even though it isn’t, like how gum sits in your stomach for 7 years?

Clearly this was a question we had to solve — with science!

My original plan was to do this all in BigQuery, but when I started searching for Billboard top 100 data in easily queryable form, I came across this dataset available over at data.world that seemed to have everything I needed. So that’s what I ended up using.

Please note that I have no affiliation with this company, but they probably have my favorite terms of service pages ever.

Getting each song’s top position

So the first step was taking this data set (which had one row for every week a song was listed in the Billboard Hot 100) and condensing it down into a list where I had each song’s top position in the charts and the date they hit that top position.

I originally had a much more detailed breakdown on how I did this, but I’m going to skip it because, frankly, it’s not all that interesting.

Now that we’ve got a pretty good data set to work with, let’s ask ourselves the more interesting question…

What makes a one-hit wonder?

My initial thought was that if you made onto the Billboard Hot 100 only once, you would qualify as a one-hit wonder. The issue here is that making it onto the Hot 100 is a realllllly generous definition of a “hit”.

Do you remember, for instance, that ‘80s classic “Night Pulse” by Double Image (#92 on the charts)? I’m going to guess not, unless you are actually a former member of the band Double Image.

It's as if Tommy Wiseau decided to direct music videos

Similarly, I consider Kajagoogoo a one-hit wonder for their song “Too Shy” (#5). But they had a second song, “Hang On Now” that reached 78. Would they technically count a two-hit wonder? Probably not. If a definition of a one-hit wonder doesn’t include Kajagoogoo, it’s probably not a good definition. Ooh, that’s good. Let’s put that in a pull-quote.

If a definition of a one-hit wonder doesn’t include Kajagoogoo, it’s probably not a good definition.

So I decided that an equally simple, but probably more accurate measurement of a one-hit wonder is to simply find any band that had one and only one song reach a rank of 40 or better. That seemed like a good cut-off, what with the the top 40 being such an American cultural staple and all.

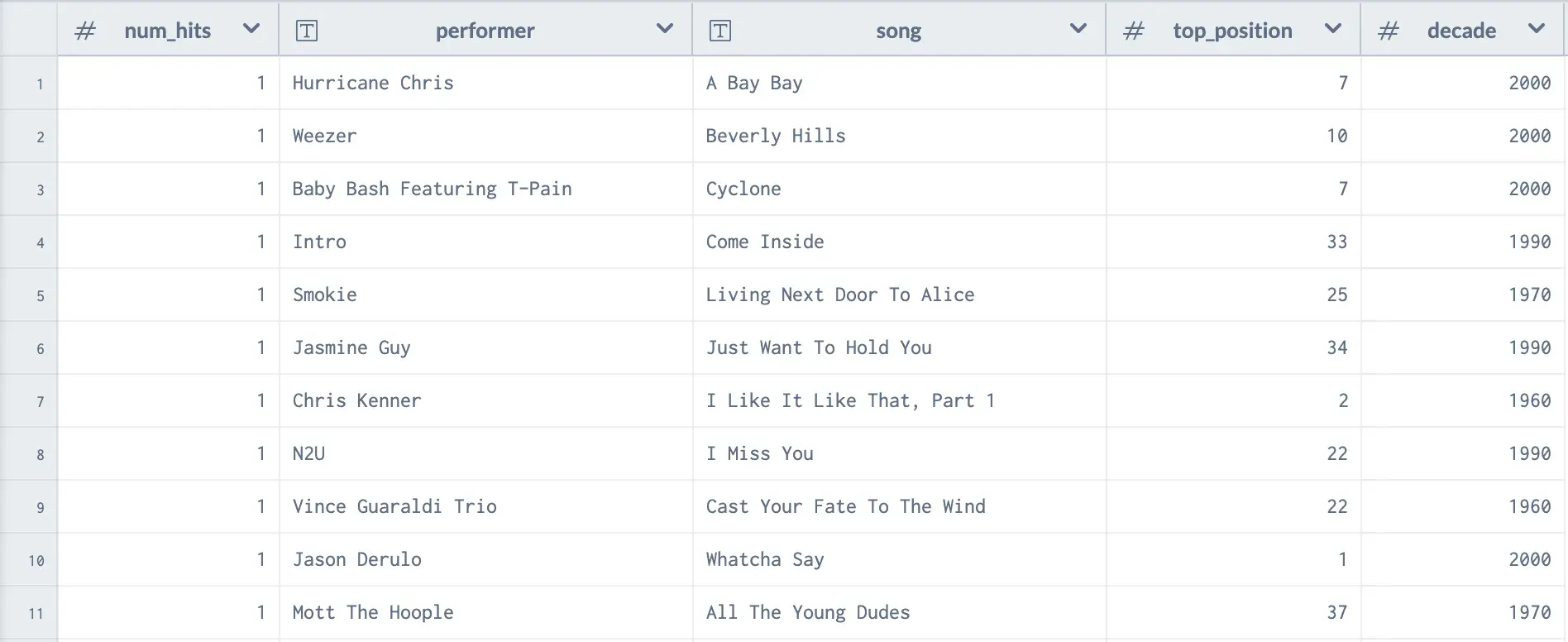

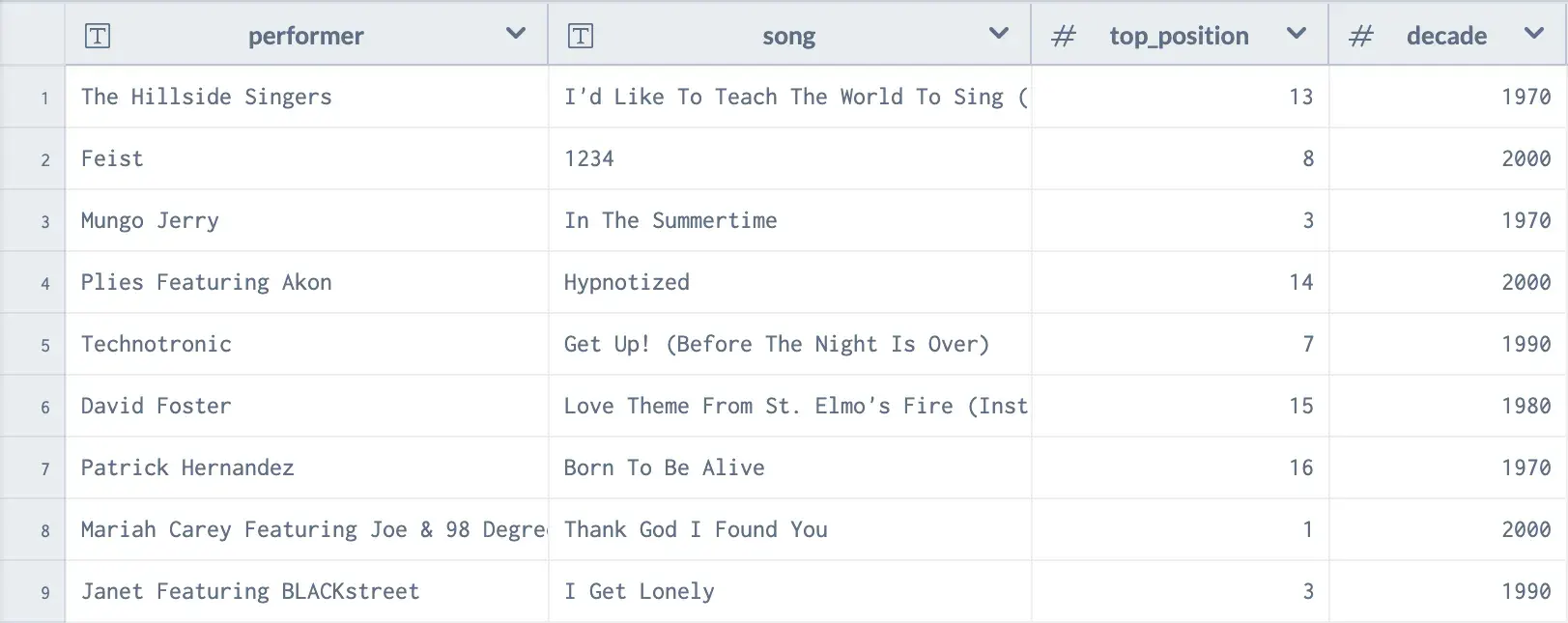

So let’s grab a list of all bands that only have one top 40 hit, along with the name of their hit song, the decade, and their top rank:

Okay, this is starting to look pretty promising.

And then, of course, it’s pretty easy to group these by decade and count them.

Biggest one-hit wonders by decade (initial findings)

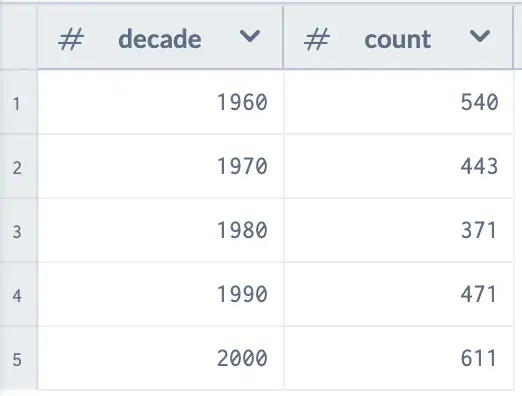

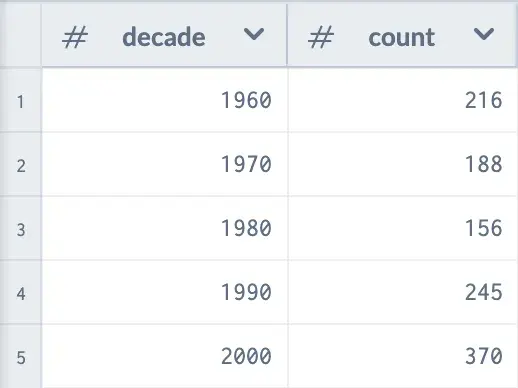

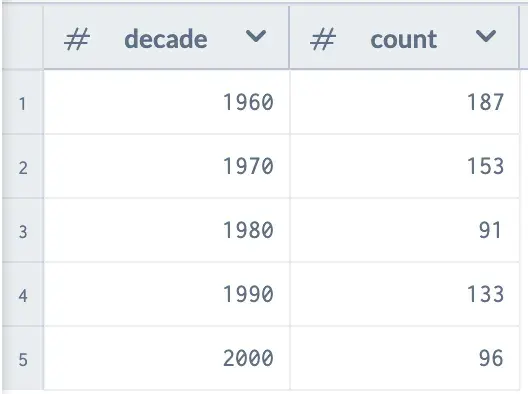

So, what did we find out when I group this list by decade?

That’s right. According to our data, the 1980s actually had the fewest one-hit wonders, while the 2000s had the most. So are we done? Can we simple point to our data, shout Whoomp! (There it is), and move on?

Well, hang on, because there are two issues with the data that I wanted to fix.

The Blink-182 problem

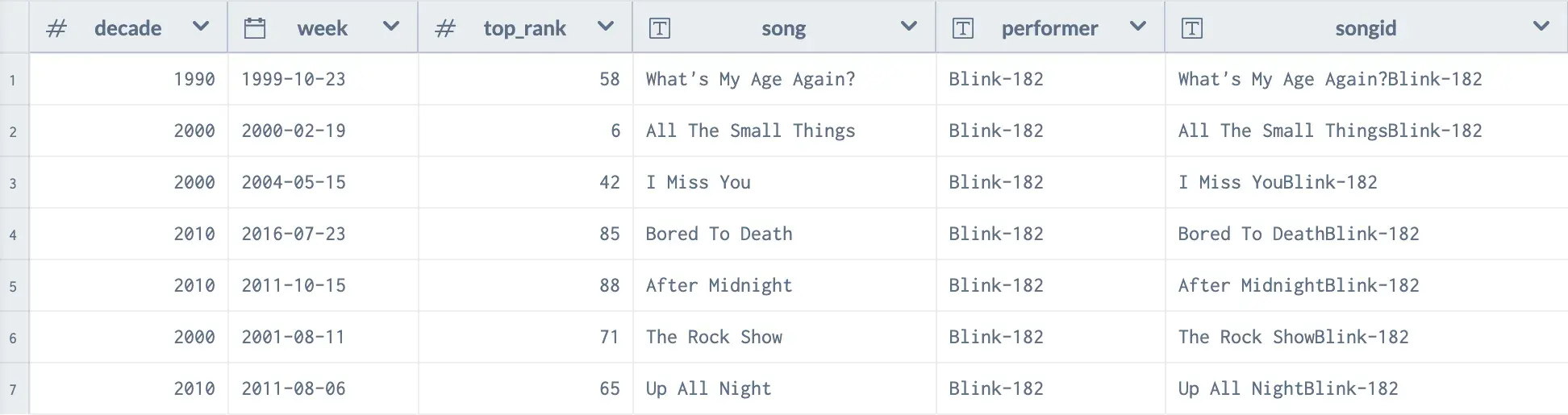

According to our initial findings, Blink-182 is considered a one-hit wonder because only one of their songs (“All the Small Things”) actually made it into the top 40. Everything else lingered in the 40s-to-60s range. That seemed strange to me.

I think a lot of this is because, by the time the 90s hit, alternative music had become more mainstream. So it was possible to have a five-time platinum pop-punk album that barely registers on the Hot 100 charts, because those singles are finding their success in the Billboard Alternative charts. I’m guessing there’s a number of country and R&B artists that also fall into this category.

But none of this really excuses the fact that there are a number of bands that technically count as one-hit wonders based on this definition that just felt wrong. This includes Weezer, Ozzy Osbourne, Missy Elliott, Beck, Rush, and Cypress Hill.

So I decided to revise my definition of a one-hit wonder to the following:

An artist counts as a one hit wonder if they have one song in the top 25, but then no other songs in the top 75.

This works out nicely in that Weezer, Blink-182, et al, are no longer considered one-hit wonders. But, most importantly, Kajagoogoo still is.

So, with a little bit of work, I was able to re-run my query to look for bands that had one hit in the top 25, and no other hits in the top 75.

This generated a smaller list of one-hit-wonders per decade (which makes sense if you think about it), but when you group them all together, you still see that the 80s has the fewest one-hit wonders.

! It’s also kinda interesting that the 2000s now have the most one hit wonders by a long shot. This actually brings us to our next problem…

The Duet Problem, Featuring Lil Cameo

If you were to browse through these results, you’ll start to notice that there’s a number of one-hit wonders that consist of duets.

Take for instance, “Ebony and Ivory”. This hit #1 on the charts and, technically, it’s a one hit wonder because the performer “Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder” never had another song that hit the top charts. This also holds true for “Kenny Rogers Duet With Dolly Parton”, which released “Islands in the Stream”. But I would not call any of these artists one-hit wonders. Not unless I want to get banned from Dollywood for life.

Uhh... on second thought... I might be okay with that.

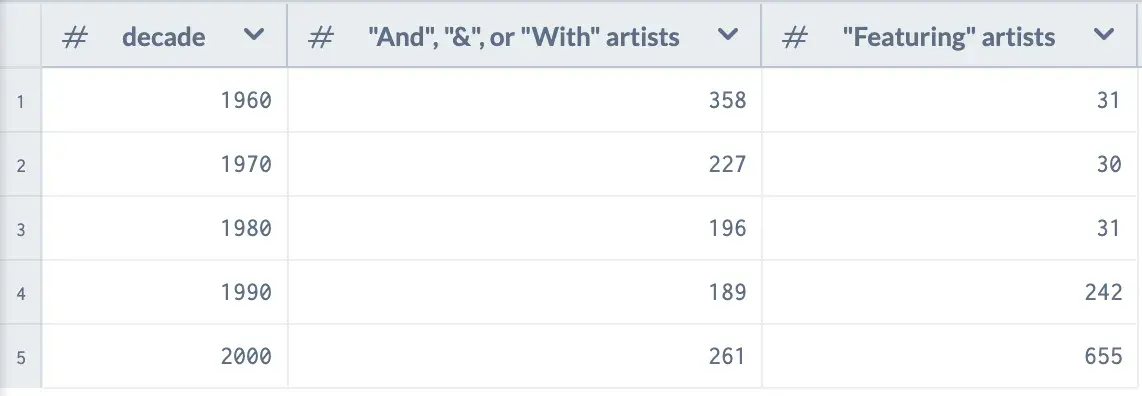

So let’s take a look at artists that have “&”, “And”, or “With” in their name, along with artists that have “Featuring” in their name.

We can see that this issue is fairly consistent across most decades (although there’s a small increase in “And” artists in the 1960s). That is, until you reach the mid 90s. Starting from there and accelerating into the 2000s and beyond, you see a huge increase of artists “Featuring” another performer.

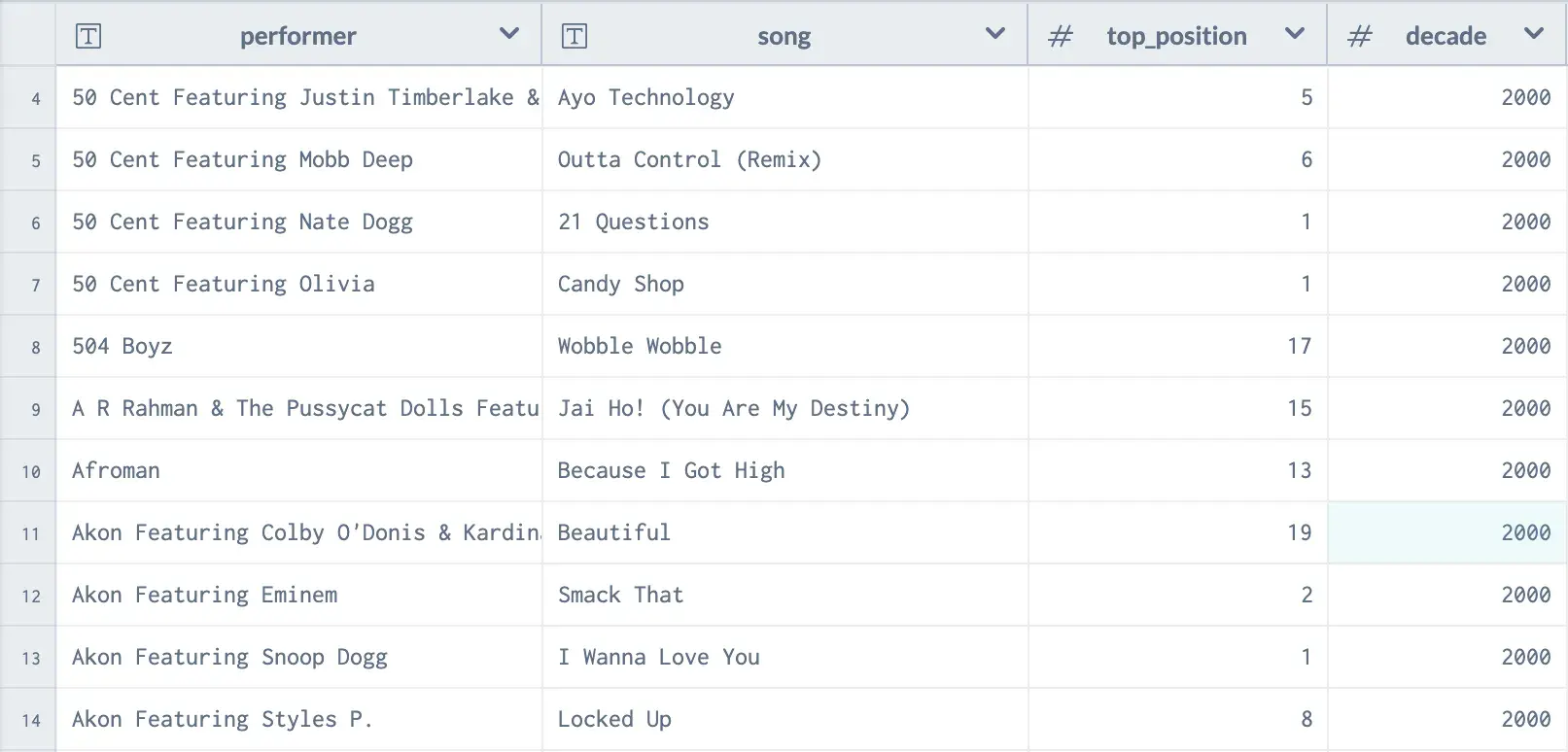

So if we were to take a look at earlier results, you can see that both 50 Cent and Akon are considered to be one-hit wonders several-times over (which I know is kinda redundant) because each one of their hits has a slightly different artist name.

Both 50 Cent and Akon shouldn't be on my one-hit wonder list. Afroman, you can stay.

Now I can address this by using a little regular expression magic to reduce any artist name that includes the word “Featuring” to just the performer listed first. This means that “50 Cent Featuring Nate Dogg” is just considered “50 Cent” for hit-counting purposes.

The problem comes with that tricky little word “And” (or the ampersand symbol, or a few other variations). In some cases, it probably makes sense to condense those down to the performer listed first. That means that you can take “Dancing in the Streets” by “David Bowie & Mick Jagger” and give full credit to David Bowie — whether he wants it or not.

The problem is, there’s no way going by the name alone to distinguish between a band name that just happens to have an ampersand in it (like “Captain & Tennille”) from a true duet (like “Aretha Franklin & George Michael”).

Now in most cases, this isn’t a big deal. You just end up with some kinda weird band names. Hootie & The Blowfish is now just “Hootie”. But in a few situations, you end up with two completely different bands getting condensed into one. For instance, 80’s band “Love and Rockets” and 70’s band “Love and Kisses” are both now considered to be the same artist named “Love”.

The good news it that this case seems to be really rare — I only found a handful of instances where two completely different bands got combined into one. And maybe if I really cared, I’d somehow find a way to manually tag these non-duet bands separately from the actual duets. But that’s more work than I care to tackle at the moment. I think for now, the benefits of combining these artists outweigh the small number of false positives

The 60s problem

One last problem that I never discussed in my original blog post is that my data set only goes from about 1958 - 2017. Why is this an issue? Well, imagine you have a band who has a couple of big hits in 1954 and 1956, and then has a third big hit in 1960. Since my data set never included those first two hits, that band would be considered a one-hit wonder. So I think there’s a pretty reasonable chance my list of 1960s one-hit-wonders is a little inflated.

In theory, there’s a similar problem with my 2000s list. If a band had a big hit in 2009, and then had another big hit 9 years later in 2018, they’d also be listed as a false positive. But that’s a pretty big gap in between hits, so I suspect this didn’t have much of an affect.

Biggest one-hit wonders by decade (final results)

So, with that said, here is my query of one hit wonders, where a one-hit wonder has at least one song in the top 25, but no other songs in the top 75, and any duet or song “Featuring” somebody else is attributed to the artist listed first.

And what does the final tally look like?

You can see that combining duets and cameos seriously reduced the number of one-hit wonders in the 2000s. The was some reduction in the 1960s, but not as much as you’d think given the number of artists with “And” in their name. I suspect (but can’t prove) this is because these artists are less often real duets, but more often bands with names like “Randy & The Rainbows”

The master list of one-hit wonders

For space reasons, I can’t include the entire list of one hit wonders here, but here’s the list of one-hit wonders, broken down by decade: 1960s, 1970, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s

But after all of that, our original results basically still hold true. The 1980s had the least amount of one-hit wonders, and the 1960s still had the most.

Which leads us to our next big question…

Why does everybody think the 80s have the most one-hit wonders?

So if the 80s has the fewest one-hit wonders, why does it seem like they have the most? I don’t really know, but here’s a few theories:

Theory #1: The 80s were just the era when we were first exposed to pop music

Maybe we all just think 80s have the most one-hit wonders because that’s the era when we were primarily exposed to pop music. Maybe if I had grown up with the music of the 60s, I’d be reminiscing to “I’m a Girl Watcher” the way I currently reminisce about “Come on Eileen”.

Or not. I don't think that song aged well

But, as my friend Sam points out, he also thought the 80s were the peak of one-hit wonders, and he wasn’t alive in the 80s. And that puts a big dent in my theory. It also makes me feel really old. Thanks, Sam.

Theory #2: The 80s had the best one-hit wonders

So if you ever check out a listicle of “Best one-hit wonders of all time”, you’ll see that they are often dominated by songs from the 80s. Could it be that maybe the 80s simply cranked out better one-hit wonders? And therefore, the decade is associated with one-hit wonders because it had so many gosh darn good ones?

To be fair, nobody can pull off a simulated bagpipe solo like The Church

I’m a little skeptical here. I might have my cause and effect mixed up. If we all walk around thinking that the 80s are the decade in which one-hit wonders were king, then when somebody polls us for a list of the greatest one-hit wonders, we might naturally just start thinking about our favorite hits from the 80s.

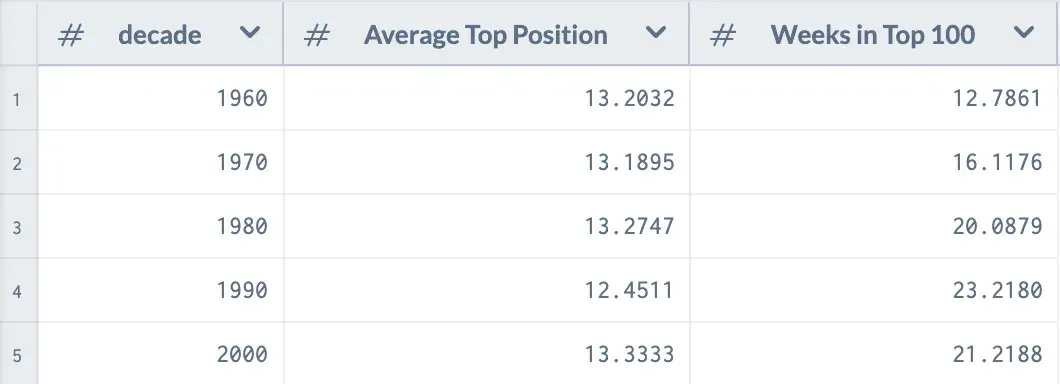

But still, it’s worth investigating. Obviously, figuring out which one hit wonders are the “best” is hard to do objectively. But as a secondary characteristic, we can look at how long each of these one-hit-wonders were in the Billboard Top 100, and how high they peaked. If a hit is good (or at least memorable), you’d expect it to stay longer on the charts or reach a higher top rating.

So what happens when we break down these stats by decade?

Huh. Well, it looks like the data doesn’t really hold up my theory. When it comes to the average top ranking, the decades are pretty similar. When it comes to one-hit-wonders staying on the charts longer, it’s true that the 60s and 70s hits were more fleeting, but it was the 90s that seemed to have the songs that stayed on the charts the longest.

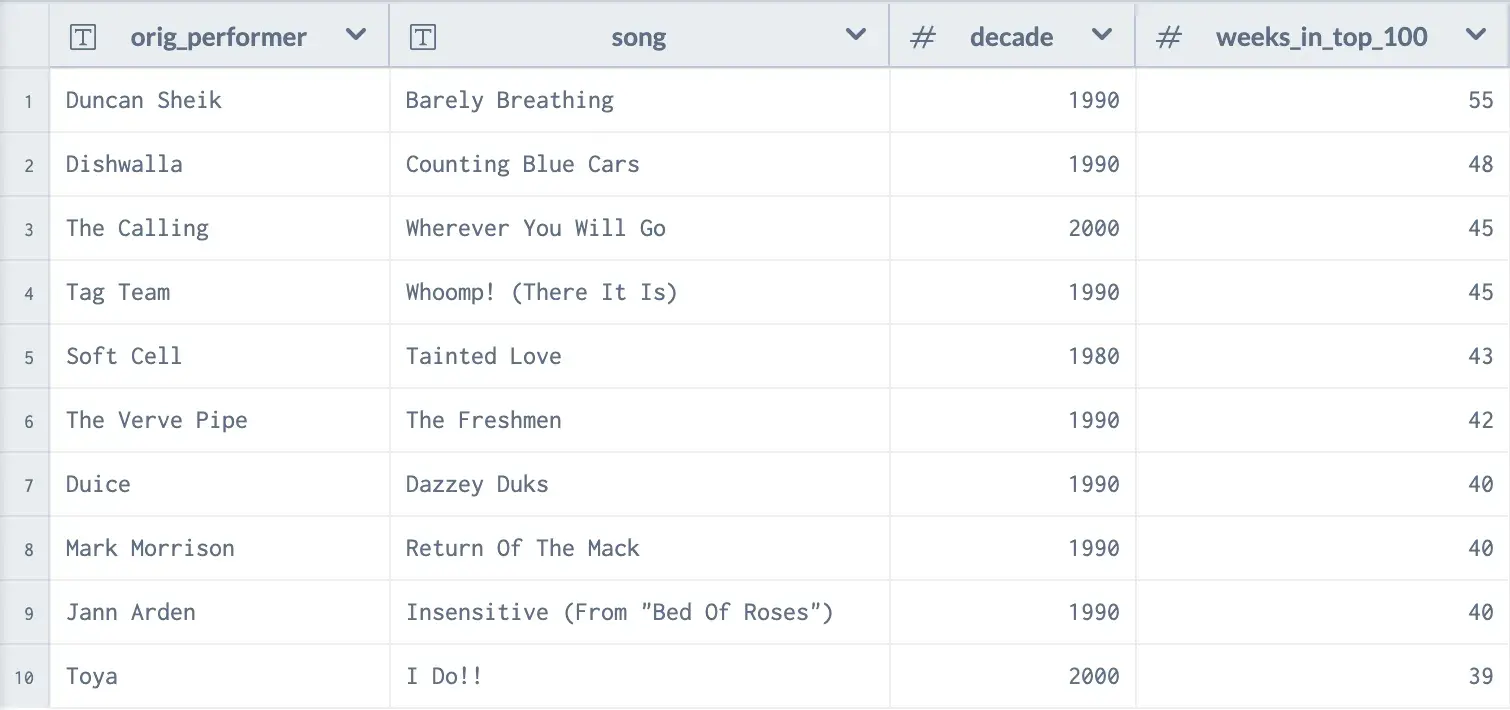

Oh, and in case you were curious, the one-hit-wonder that was on the top 100 for the longest period of time? Duncan Sheik’s “Barely Breathing”, which was on the charts for a full 55 weeks.

Also, if you haven't ever listened to the acoustic version of Barely Breathing, you really should.

Theory #3: Video killed the radio star

My final theory is that MTV is somehow responsible for all of this.

If you think about it, the 80s were the era when MTV was at its peak of music video influence. The network was becoming more and more popular, but reality shows hadn’t taken over yet, so the majority of the programming was actual music videos. And (hi, kids!) this all happened before YouTube was around.

This means that, unlike the 60s and 70s, we noticed one hit wonders a lot more because we didn’t just hear them on the radio; we saw them in our living rooms every day, and were exposed to the bands behind the music — not just the songs.

But unlike the later 90s and 2000s, there were no other alternatives for watching music videos, much less getting to choose which videos you got to see. If you wanted to watch a music video, you really only had one choice (okay, two if you count VH-1), and it was primarily pop music.

So maybe the reason we all remember the 80s as the era of one-hit wonders is because that’s when they were front-and-center in our living rooms, and the phenomena became that much more obvious. Then, that designation just stuck around and influenced future generations.

It's probably also the reason most Americans think A-ha was a one-hit wonder, even though they're not (see below)

I don’t know if this is right — but it’s my best theory so far.

Other Fun Facts

What are the biggest one-hit wonders of all time?

There’s a lot of great one-hit wonders throughout history, but who’s the most one-hit-wondery? I decided to come up with a list of artists that a) Had a song hit #1 in the charts, but then b) Never had another song show up anywhere on the top 100 ever again.

Here they are, in order of most time on the charts…

Bands that weren’t one-hit wonders that I kinda thought were

There are several bands who aren’t one-hit wonders because they had other smaller hits that I forgot about:

- A-ha had “Take on Me” (#1), but they also had “The Sun Always Shines on TV” (#20) and “Cry Wolf” (#50)

- Dream Academy had “Life in a Northern Town” (#7) but they also had “The Love Parade” (#36)

- Katrina and the Waves had “Walking on Sunshine” (#9) but they also had “That’s the Way” (#16) and “Do You Want Crying” (#37)

- Big Country had “In a Big Country” (#17) but they also had “Fields of Fire” (#52)

- Extreme had “More than Words” (#1) but they also had “Hole Hearted” (#4)

- Dead or Alive had “Spin Me Round” (#11) but they also had “Brand New Lover” (#15)

Likewise, there are several bands who aren’t one-hit wonders because their songs weren’t as big of a hit as I thought. Possibly because I was looking at “pop” charts, and a lot of these feel more alternative / new wave.

- “Video Killed the Radio Star” by the Buggles only peaked at #40

- “Melt With You” by Modern English only peaked at #76

- “There She Goes” by The La’s only peaked at #49 (but the Sixpence None the Richer version peaked at #32, preventing that band from being a one-hit wonder)

- “Crash” by The Primitives, “Closing Time” by Semisonic, and “Standing Outside a Broken Phone Booth With Money in My Hand” by the Primitive Radio Gods didn’t even make it onto Hot 100 charts. Hearing that news made me… downhearted, babe.

An explanation for why the 90s provided us with the surprisingly similar one-hit wonders “Whoot, There It Is!” by 95 South and “Whoomp! (There It Is)” by Tag Team, and why the latter proved more memorable in the long-term

I have discovered a truly marvelous demonstration of this proposition that this blog post is too narrow to contain. (But it probably has something to do with the bassline.)

Wrap it up already, why don’cha?

So there ya go folks; everything you ever wanted to know about one-hit wonders but were afraid to ask. If you’re interested in playing around further with the data, go ahead and check out the project! Maybe you’ll find some insights that I haven’t discovered. After all, everybody’s got to learn sometime.